Programme 2 | Inspire – The Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence

So how did we go about it?

In our second programme of public engagement, community members wished to hold accountable organisations that used artificial intelligence in products and services that interacted with humans. The idea of a People's Charter for Artificial Intelligence emerged through the idea sessions described in Programme 1.PEAs include Rochelle Taylor (MMU), Ngozi Nneke (University Academy 92), Femi Stevens (Self employed) and Shobha Gowda (University of Salford and University of Manchester), Helen Kirby-Hawkins (MMU) and members of the project team Keeley Crockett and Sara Linn took part in this programme.To support this programme, the PEAs and Team members met weekly or fortnightly for an hour to prepare for each session, feedback on allocated tasks and monitor if the project was on track and in budget.

Levenshulme Inspire (https://www.lev-inspire.org.uk/) is a community organisation that brings people in the community together through a wide range of activities and an amazing community café. It’s a place where people can connect, learn, work, and find support to achieve their goals.

Levenshulme is in the Northwest of the UK with a population of over 19,000 [https://citypopulation.de/en].

Onboarding

Three additional on boarding sessions were held to ensure that every new community member had the opportunity to find out about the PEAs in Pods project and the programmes of public engagement and the ability to ask questions and raise concerns before joining the co-production sessions.

Our original brief was co-created with community members from a series of ideation sessions which were described in Programme 1. The brief was to develop a Citizens Charter for Artificial Intelligence. During the co-production sessions, the Charter became known as “The Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence” to be more inclusive to all.

The idea of creating a Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence was voted upon by community members as a way to ensure that everyone got the same level of service when using any digital application that used data and subsequently used artificial intelligence in decision-making.

Charter Research

Community members asked PEAs and the Team to conduct initial research into other charters that existed in the United Kingdom and provide some examples as a starting point. Some of the ideas in the existing charters could be used as scaffolding and to give further ideas onto the content and structure of the People’s Charter for Artificial Intelligence.

The original Citizens Charter was for Public Services in 1991 and was an initiative by the Conservative government under John Major to improve the quality of public services and the relationship between citizens and public services (House of Commons – Public Administration – Twelfth Report).

The charter comprised of a number of principles of public service including standards, openness, information in plain language, choices, non-discrimination, accessibility and the entitlement to a good explanation if things went wrong.

Other research conducted looked at numerous charters including, digital citizenship charters, the Parliamentary and Health Service Charter, Department for Work and Pensions Customer Charter, The Department of Education Staff Wellbeing Charter, the Metropolitan Police Charter, Northern Rail Passenger’s Charter, Advanti West Coast Passengers Charter and the National Lottery Customer Service Charter. Community members looked at these charters and decided on what elements were good in terms of providing a service or product. We used a series of coloured stars for community members to flag different parts of the Charters that they felt represented good service.

The co-production sessions included:

- Design of the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence and who it was aimed at.

- Development of the principles of the Charter and what good looks like for community members

- Testing ideas and solutions

Co-Production Session 1

Questions explored during the first co-production session were in hindsight too ambitious. We had planned an approximate time for discussing each question, but this was not practical as we wanted to ensure that all community members participated equally in the design conversation. The original questions were:

- What would the aim of the citizens charter for artificial intelligence be? What would community members like this to achieve?

- Who would the citizens charter for artificial intelligence be for? Who would it not be for?

- What do community members see as the positive consequences of having a citizens charter for artificial intelligence?

- What should citizens expect when they are using a product or service that utilises artificial intelligence?

- Who would community members like to give feedback on the charter as it was being designed?

- Looking ahead if an organisation agreed to sign up to the charter what does it actually mean for the organisation? Should they for example get a badge on their website? How do we know if they are sticking to the principles of the charter?

We developed several activities to explore the questions above. For example, to explore the question “What should citizens expect when they are using a product or service that utilises artificial intelligence?”, we took prompts from the original 1991 Citizen Charter:

- Standards of Service

- Openness

- Quality

- Accurate and correct information

- Choice

- Explanation

- Value

and asked the community members to pick one and expand in the context of responsible artificial intelligence, for example, what does a good Standard of Service mean in the context of online banking?

Co-Production Session 2

Our second co-production was designed to do a deeper dive into what our community members wanted the principles of the Citizens Charter for AI to look like.

After an overview of the session, breakout interviews were conducted in small groups to ensure that everyone’s opinion was captured. PEAs and the team had developed a series of questions in advance of the session, but allowed for flexibility. We learnt that quieter community members felt more confident speaking their opinions in smaller groups. A snapshot of selected insights are shown below:

Q1: Do you think the name of the charter – Citizens Charter for AI is appropriate?

On analysis of the responses, suggestions from community members were summarised as

- Citizens Charter for AI

- Citizens Charter for AI and Data protection

- Citizens Charter for Trustworthy AI

- The Peoples Charter for AI

- The Peoples Charter for Data and AI

Some members of the community felt that the word Citizen was not inclusive and preferred the use of the word “People”. It was also felt that “Trustworthy” should not be in the title as “trust was something that had to be earned and personal”. Data was a very important topic in the conversation, but community members felt it was implied within AI. Following a group discussion and vote – the Charter would now be referred to as The Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence.

Q2: What in your opinion should the AIM of the ‘Citizens Charter for AI’ be? What should be its purpose? E.g. to protect a person’s rights with regards to data and how it is used in AI applications?

Community members agreed the initial aims on the charter which were:

- To make everybody aware of AI, automation, and how their data is used.

- To protect a person’s rights with regards to their data, how their data is used within the AI system and to ensure that it is secure.

- To make businesses and organisations explain to people what is their rights when AI is used and how the business and organisations protect them.

In the group discussion, some of the challenges explained by the community concerned the existing communication and use of data by businesses and organisations. For example, the community were concerned with the small print that no one ever reads especially in terms and conditions and privacy notices. What is needed is clear details about the use of data and artificial intelligence that are “in your face”.

Q3. If an organisation chooses to adopt the ‘Citizen charter for AI’, should they have a logo/certificate/badge to be displayed on the website/ printed etc. If you saw such a logo would you feel more confident in using that service?

All community members felt that a logo was important, and organisations should be open to scrutiny/establish legitimacy when asked how they comply with charter principles. A logo could be on an organisation’s website, but it also could be on a poster in a shop window. Community members shared an example of the Inspire Task Force “Take a Chair” initiative. Local shop owners could display a poster in their window if they had a chair in the shop so that people could come in and rest and sit down if they needed it.

The second activity of the session was to discuss and vote on ideas for ten draft principles which were created as a result of the first co-creation session and were designed to explore what a good standard of service looks like for an organisation that utilises AI. These ideas along with the analysis from the interviews would be used to produce a first draft of the Peoples Charter for AI.

It was very important to community members not to abbreviate AI – but to say Artificial Intelligence. This was supported by a round table in a rural community held after Programme 2 had been completed, when members of the community shared that AI in their farming community typically meant Artificial Insemination!

Language was important, as the Charter principles were developed, community members replaced AI within the principles with “Artificial-Intelligence based systems” as this better reflected what they understood by AI.

Community members decided that they would like a logo to be designed for the Peoples Charter for AI. They wished the competition to be open to everyone, regardless of age in the communities of Inspire and The Tatton and that vouchers should be offered as prizes. Community members also wanted the funder, EPSRC, to judge the competition anonymously. The Team had the greatest set of actions for this activity, with the principal investigator of the project undertaking research into competition terms and conditions before obtaining institutional ethical approval.

At the end of the second co-production session, we received some feedback from community members that some members of the community felt they were not getting the opportunity to speak. We therefore co-developed Codes of Engagement which we presented at the start of each subsequent session.

Codes of Engagement

Codes of Engagement

Co-Production Session 3

The aim of this session was to reflect on the analysis of the interviews and activities of the last session and to co-produce together the first draft of the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence.

We started the session with the Code of Engagement to ensure that everyone had opportunities to speak freely without interruption. Following a brief reflection on the aims of the charter and who the charter was for, we started to co-produce the principles of the charter to together as a group. As a starting point (based on the last session), we had a series of slides, one for each draft principle and explored as a group what this principle could mean in practice to community members. For example,

Draft Principle:

When an AI is used, should it maintain consistent standards of service across different communities and user groups.

Activity:

What does consistent standards mean to you?

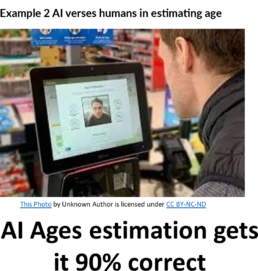

We also integrated other activities to explore community perceptions at a deeper level. For example, to explore the Draft Principle: An AI should provide accurate and correct information on how it makes a decision, we discussed two examples with community members:

Example 1 AI verses humans in detecting potholes on a road.

Using examples that the community members had themselves brought up in the ideation session provided a great way to discuss accuracy of applications that use AI. As we co-produced the different principles, we incorporated lots of examples of AI including the NHS (supporting doctors in diagnosing medical conditions) and Amazon (making recommendations of products that you might like to buy).

For the Draft Principle: Organisations should have a duty of care to communicate clearly when an AI decision is wrong, we explored with community members what they would like to know when AI gets it wrong? Duty of care was very important and all community members felt that human contact – the ability to have a conversation with a human was very important.

Accountability was also very important if there was to be trust in using the service. We also discussed what reasonable adjustments could be made by organisations that use AI. It was felt that applications and services of AI should be accessible to everyone regardless of background, language, level of digital literacy and for those experiencing digital poverty. The strongest message was that a human should always be available for people to have a choice.

The second part of the co-production session was a presentation of the community demographics which was based on research undertaken by the PEAs. The idea was to ensure that when developing the Charter we were inclusive to the people within the communities and beyond.

The last part of the co-production session looked at defining values and priorities in the Charter, where we captured ideas through discussion and voting.

Community Members Values and Priorities in the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence

Values: ethical use of artificial intelligence, transparency, inclusivity, privacy protection and security of data, fairness and equality, community empowerment, accountability, sustainability.

Priorities: education and awareness, community engagement, bias mitigation, data ownership and governance, job displacement, environmental sustainability, collaboration, safety and security.

Logo Competition

Community members required a logo to be developed for the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence. The facilitate this, it was decided to have a community competition open to all members of the community with prizes!

We first launched the competition in communities using posters. We also left paper copies of how to enter the competition and terms and conditions in both The Tatton and Inspire community cafes and relied on our community members to promote. After two weeks, we got only 2 entries. We discussed this with community members who advised us to have in person sessions where we were there so we could explain in simple terms about the competition, but more importantly about the Peoples Charter for AI. .

A real barrier was the length of the Terms and Conditions document for the competition, which was signed off by the University legal department. By holding in person sessions in communities, we were able to explain this in a simplified way and people could ask questions.

Community members specifically requested that the funder (EPSRC) judged the entries to the logo competition anonymously.

We advertised two Draw a logo sessions in both communities. An example poster can be found here:

A competition Terms and Conditions document was created and signed off my the MMU legal department and additional institutional ethical approval was granted. In total 22 entries were made and these were anonymously sent to the funder of PEAS in PODs, EPSRC for judging. The entries were judged on:

- Relevance to the aims of the People’s Charter for Artificial Intelligence

- Originality and Creativity.

- Clarity and Simplicity.

- Inclusivity.

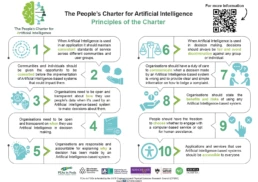

The images below show the winning entry as judged by the funder.

Co-Production Session 4

The aim of the 4th Co-production session was to

- Explore what does good look like for you and your communities for each of the principles for Citizens Charter for Artificial Intelligence

- What actions would you like organisations to do to ensure they abide by the principles of the charter?

- Co-produce a pledge for organisations.

Together we explored what good looks like for community members for each of the principles co-produced during the last sessions. For each principle, we created 2 – 4 questions that community members might want to consider, for example for Principle 1: When Artificial Intelligence is used in an application it should maintain consistent standards of service across different communities and user groups, what would community members want the organisation to do to show they were given a consistent standard of service? . During the session, there was also opportunity for community members to tweak the wording of the principles to ensure they represented their voices.

Based on previous sessions, the community thought it was important to hold organisations who wish to adopt the charter accountable. We discussed should we co-produce a Pledge to allow organisations to work towards achieving the Principles of the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence and we looked at what a pledge might look like.

We all recognized that the work required to co-create such a Pledge and engage further with wider community members and organisations is a separate project. However, included initial insights into what the Pledge might look like and included this in the Peoples Charter for AI Explainer booklet. The next stage is to try and promote this to businesses and organisations!.

Co-production of the Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence was the first step in a longer journey to start holding organisations accountable for the use of artificial intelligence in their products and services. The commitment of community members, the PEAs and the Team was way over what was allocated in the original project and it was felt by all, that given time constraints, the Explainer booklet was a natural place to end this programme of public engagement. We are exploring further funding and on the look out for organisations who are willing to take the pledge!

The winning entry by Patu (Inspire community) is shown below, along with the final concept co-produced with Masters student Rujula Niraipandian Sudhakaran.

The co-produced Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence is available as an Explainer booklet and also as an infographic. The Charter can be referenced and cited as Professor Keeley Crockett | Manchester Metropolitan University, Dr Rochelle Taylor | Manchester Metropolitan University, Dr John Henry | Manchester Metropolitan University , Thorpe, Matthew, Ngozi, Nneke, Kirby-Hawkins, Helen, Gowda, Shobha, Stevens, Femi, The Levenshulme Inspire Centre and The Tatton Community Café (2024) The Peoples Charter for Artificial Intelligence. Documentation. Manchester Metropolitan University, Published Version Available under License Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives. URL: https://doi.org/10.23634/MMU.00637617

Our Explainer booklet introduces the charter, outlines what good looks like for communities in achieving the principles of the charter, and provides guidance to organisations who would like to work towards achieving the principles of the Charter.

The People’s Charter for Artificial Intelligence infographic is available to download in several languages.

Compensating Communities

Community members were paid £15 per hour for their time using One4All vouchers, which could be spent online or in stores. Refreshments, including lunch for full-day sessions, were provided. Public transport costs were covered, and there was a budget for taxi expenses for people with disabilities who needed them to get to the venue.

Considering Ethics and Consent

In ensuring members of the community were taken care of, and that the data collected and used to to communicate was handled in line with data legislation (e.g. GDPR), MMU and Noisy Cricket worked with Back on Track to protect both the community members who choose to participate and academics in working with them.

MMU and Noisy Cricket ensured:

- Safeguarding and support measures were in place for the people participating in the research should they need support beyond the scope of the project

- Informed consent frameworks were utilised so that community members were clear on what the research involved, any potential benefits and risks as well as the right to withdraw from the research at any time

- Transparency and accountability through conversation and documentation around why the research was being conducted and how it will be used, plus managing expectations around the long-term aims of the project

- Inclusivity through reaching, engaging and balancing the voices of diverse groups, and that information shared and explored is relevant and accessible, as well as facilitation of voices is equitable, especially with marginalised groups

- Rigour in designing ongoing ethical research approaches and methodologies, to respect the social and cultural factors influencing communities, and considering potential biases which might influence the research process

- Reduction of risk through monitored research performance, from adhering to data privacy regulations and minimising unintentional harms to navigating complex situations and addressing power imbalances, to avoid legal issues and support academics in learning and evolving best practice

Exploring Power Dynamics

To help the academics better engage with people affected by homelessness throughout the HI Future Programme, Noisy Cricket held a series of workshops to help them understand how power and privilege shape our views on homelessness and employment.

The PEAs explored:

- Who is accountable and responsible for recruitment and AI ethics in the HI Future program, and who should be consulted and informed about its potential impacts during the Public Engagement Programme.

- Mapping their shared goals, objectives, and values in exploring the project, and any challenges or opportunities that could affect their ability to respond successfully.

- How to address the assumptions and ideas they developed about AI ethics in social mobility recruitment when working with people impacted by homelessness.

- Reflecting on the wants, needs, and hopes of people affected by homelessness in using machine learning to help them find jobs that match their strengths.

- What steps should be taken to make sure the community’s voice is central, trust is built, and value is created for the people involved in the HI Future Program.

Organising and Delivering Workshops

Along with planning agendas, organiSing activities, leading discussions, and capturing key points, the PEAs, MMU, and Noisy Cricket team worked hard to create a warm, welcoming, and safe space where community members felt comfortable participating.

Key actions included:

- Booking meeting spaces in familiar, well-lit locations and offering a range of hot and cold drinks as well as snacks to cater to different dietary needs and preferences. For the HI Future project, this meant reserving a room and arranging catering through Back on Track, which also helped support the charity financially.

- Sharing information about the next session’s time, date, and location at the end of each session. They sent reminders through Back on Track staff and followed up with more details by email or phone, using the communication method chosen by the participants during sign-up. This helped keep attendees informed and encouraged them to attend.

- Giving community members control by regularly asking for consent to take notes or photos at the start of each session. At the end of each workshop, participants were invited to reflect on what they learned and how they felt about the session. By choosing to join in, they gave their permission for their feedback to be recorded.

- Clearly setting expectations at the start of each session helped create a safe environment. This included agreeing on speaking rules (e.g., one person speaks at a time), how participants could signal they wanted to speak, making sure everyone had a chance to contribute, and managing time. The group also discussed what topics were appropriate to talk about in advance.

PEAs needed to stay present, pay close attention to each other and the community members, and ask questions or offer reflections to better understand different viewpoints. It was also important for them to remain flexible and open to any unexpected ideas or new directions that came up during the sessions.